PAPUA NEW GUINEA

THE CAMEL TROPHY 1982

Timing is Everything:

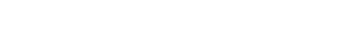

In 1980, I’d canoed the beginning tributaries of the Amazon River, and in the early part of `82, wondered what might be my next expedition. While presenting my collection in Las Vegas at an outdoor trade fair I met Yvon Chouinard, the creator and owner of Patagonia. I asked him what he thought might be the remotest area in the world to plan an adventure. Yvon inquired asked what I’d done previously and upon sharing my experiences in the Amazon, he stated that the only place to go would be Papua New Guinea. He spoke about stone age tribes still existing in the highlands, and I immediately knew I’d found my adventure. Incredulously, only a few weeks later I picked up a Sports Illustrated magazine, which ran an advertisement sponsored by Camel GT Racing and British Leyland Land Rover, announcing tryouts for an American team to compete against drivers from the Netherlands, Germany and Italy in a 1,500-mile rally through the highlands of Papua New Guinea. It was too good to be true! The only problem was that the application deadline had come and gone two days prior.

Never one to ponder lost opportunities or closed doors, I reached out to a fellow Idahoan, by the name of Kenny Hamilton, who appeared in the local newspaper the same day I’d read about the rally. Kenny was the first person from our state to pass the Indianapolis 500 rookie test, and was set to race the coming Labor Day. I called Kenny to introduce myself, and asked if he’d be interested in trying out with me as co-drivers for the Camel Trophy tryouts. My thinking was that he’d do the lion share of the driving and I’d be the navigator. Kenny was game for the challenge but stressed that his sole experience was flat track, and that off Road would be totally new for him. I hurriedly put together a press kit of sorts and sent it to the NY address advertised in the periodical, replete with photos of my Amazon expedition, fashion articles and Kenny’s write-up as a professional Indy pilot. Within two days I received a phone call from the races organizers advising that Kenny and I were invited to go to Sears Point, outside of San Francisco, where we’d compete against a field of 30- other men; the field was to be narrowed down to four representing America.

Quote from the Camel Trophy Website:

By 1982 Camel Trophy had attracted interest from a number of other countries and was well on the way to becoming a truly international event. For the third Camel Trophy, two teams from Holland, Germany, Italy and the United States participated.

The location selected was the island of New Guinea, lying to the north of Australia, or more precisely, the eastern half of the island, Papua New Guinea. Covering an area of more than 460,000 square kilometers with a population of 3.5 million people made up of approximately 700 different tribes, this was an ideal Camel Trophy location: vast, sparsely populated, remote, exotic, challenging and tough.

The Try Out:

We and the other competitors were housed in the San Francisco Hyatt Hotel, where a cocktail party was held the evening before the three-day tryouts. There we met renowned racers, such as Malcolm Smith, one of America’s foremost motocross riders. He’d won the Baja 500 five different times and with Steve McQueen starred in the documentary On Any Sunday, nominated for an Academy. It was credited as the best and/or most important motorcycle documentary ever made. In addition, Malcolm won eight gold medals in the International Six Day Trial, the European cross-country event, and was a six-time winner of the Baja 1000.

Smith and McQueen

Upon introducing myself to the revered sportsman I jokingly advised that he was of little concern to me, I’d never heard of him before that night! He smiled good-naturedly with the serenity of a man who knows he’s the best at what he does and is confident in his abilities.

Also in attendance was Rod Hall, legendary Off-Road Motorsports Hall of Fame inductee whose string of 35 consecutive race wins in the early 1980s remains the longest unbroken string of race victories in off-road racing history. If not before, it was clear to Kenny and myself that we were well over our depth.

Each pair of co-drivers were assigned the same room, Kenny and I both retired around 11:00 PM, so as to try and get a good rest. However, at 3:00 AM I was still wide awake. Wondering how Kenny was fairing I whispered, “Hey pal, are you sleeping?” His immediate reply was more of a statement than a question; “What are we doing here!” The only solace I felt, which I kept to myself, was that at least HE was the one who’d be driving; all I had to do was navigate…or so I thought.

At 6:00 AM we were greeted by a cold and rainy morning, entering the team bus we noted that several of the competitors wore Nomex fire-retardant suits and had crash helmets tucked under their arms. While pondering my attire consisting of jeans, T’shirt and a nylon windbreaker, Kenny again reminded me that he’d only raced flat tracks. Deep in the throes of these thoughts a man representing Jeep USA, stood up at the front of the bus with a microphone stating that he had prepared the course we were about to take and that it was the most difficult he’d ever designed. He told us that the crumbling terrain and mountain slopes were particularly bad because of the worst rains and flooding since 1955.

“A major winter storm originating over the Pacific Ocean moved through central California in early January 1982. As much as 16 inches of rain fell in Marin County and 25 inches in the mountains bordering Santa Cruz County. The January 1982 flood was the largest since the flood of December 1955...”

Directly after the course description, the head of Camel GT Racing advised that each man was to drive the course and do so separately from the teammate we’d come with. With those words, my stomach took purchase in my throat!

In time, we reached Sears Point and climbed a couple of stories into a control tower/warming hut for a briefing. Because the tryout was broken down into three days I figured odds were good that I might be one of at last to drive, and therefore could learn from others. I entered the restroom and couldn’t have been in a better venue as a loud rollcall announced, “Robert Comstock will be number three on the course.”

The Course:

Only days prior to our arrival in the Bay area, I decided to visit a specialty off-road store in my hometown by the name of Buck’s 4-Wheelers, to try and get some pointers from Buck himself. Up until the tryouts the extent of my experience with off-roading was in an old Willy’s Jeep, which I drove throughout high school in the mountains of Idaho. Buck advised what he thought the challenges might be, one of them being water. He wisely told me to have my co-driver stand on the back bumper of the vehicle and for me to place the four-wheel-drive into compound low and shift into third gear. “Then," he continued, "you know that sweet spot you feel on particularly deep snow or heavy mud when you realize that speeding up or slowing down will completely get you stuck?". I nodded yes… "Simply motor through without stopping until you reach the end.”

As I left the warmth of the tower and began my descent down the steel steps, I thought to myself that the terrible conditions wrought by the rain would only hinder the experts and help me. With no one in earshot, I said out loud in a volume only I could hear, let’s do it. I was assigned a passenger I’d not met previously, but he was amenable to try whatever I suggested. The first obstacle was a grouping of boulders around 16 feet high that we had to climb up and over, followed by a series of switchbacks with heavy mud roads that lead around a sweeping turn emptying onto a large pond around 40-yards in diameter and three feet deep. Relying on Buck like my only parachute, I instantly instructed my companion to jump onto the Jeep’s bumper and hold on as I put the vehicle in compound load, third gear and miraculously found the sweet spot that Buck had referred to. Out of the thirty drivers I was one of the only two men to make it through.

Making the Team:

Upon completing the 3-days everyone returned to their separate areas of the country and waited for notice in the mail. In what could only be described has happen-chance, my dear friend Paul Haven a fireman paramedic with whom I’d paddled down the Amazon, also tried out and was selected. Of the four men to be selected, Paul and I were selected as teammates for the rally ahead.

Participating Countries:

Germany 1 – Werner Weiglein & Peter Reinhold

Germany 2 – Franz Murr & Wolfgang Eggers

Holland 1 – Hans Bronsgeest & Ernest van Arendonk

Holland 2 – Willem de Bruyn & Hans Prudon

Italy 1 – Cesare Geraudo & Giuliaro Giongol

Italy 2 – Giorgio Landi & Lorenzo Loreti

United States 1 – Rob Comstock & Paul Haven

United States 2 – Bob Peters & Ken Arnold

Within a month the four Americans were flown to Berlin, Germany, where we met up with the other countries’ drivers to test new Range Rovers in extremely demanding terrains.

Getting There:

From Germany, we were flown to Manila, for a 14-hour layover and a short stay in a downtown hotel. We awoke to a phone call from the lobby horridly advising us that we’d slept through our 1:00 AM alarms and that the other teams were already loaded on the airport bus, we scrambled and made the airport to board an Air Niugini flight in darkness. In a short while we were sailing amongst a forest of clouds outlined with the luminance of a full moon. As we sat in the darkened cabin transfixed by the view, a stewardess approached asking if we’d care for something to drink. Looking up we gazed upon a sight equally as mesmerizing as the one outside our porthole, her face was adorned with an astonishing array of intricate tattoos. If not before, we were now certain that the unknown awaited us.

Arriving in a sunny Port Moresby we met up with the Rally’s support staff of multinational photographers, videographers, mechanics, medics, editors of various worldwide publications and PR personnel. One of them had purchased a local newspaper that was handed from seat to seat as we flew from the sea-level of Port Moresby to Mt. Hagen’s 5,501-foot altitude; the front-page headline announced: Tribal Klansman Beheaded in Fight.

Arrival in Mt. Hagan:

Stepping onto terra firma we were met by locals with faces painted in primary fire-engine red, blue and yellow, and every secondary color possible.

The attire was akin to a Red Hot Chili Pepper Concert, with the men’s townsfolk wearing elongated gourds covering their genitalia, and long leaves protecting their backside.

That evening under the light of kerosene lanterns, the teams were assembled for an overview of the course and rundown on what to expect the following morning and start of the Rally. We knew we were in for a challenging climb, the highest peaks reach 14,793 feet. And, the higher we’d climb the more remote would be the villages. We did in fact come upon stone age tribes that had never before seen an Anglo-Saxon. There was good camaraderie amongst the teams, but from the first night on we felt closest with the Italians.

Should we accidentally hit a pig we were instructed not to stop, the tribesmen prize them so highly that we could lose our lives over such an infraction.

Interfacing with the neighborhood:

At the close of the meeting most drivers returned to their tents, however, my co-driver Paul and I were fixated on the Southern Cross and closeness of the stars overhead. Sharing one earbud each from a Sony Walkman, we walked down a path in shorts and flip-flops listening to Walking The Dog by the Rolling Stones. In time, we came upon a large group of people chewing Betel Nuts. Observing the jovial crowd for a while we noted the repeated process whereby an individual would place a nut in his mouth, and begin to chew while inserting a mustard stick (similar in look and shape of a green bean) into limestone powder (from ground coral) and masticate stick and nut together. All of a sudden one of the squatting men took me by the wrist and pulled me down on my haunches. Excitedly he placed a betel nut in my mouth, inserted a mustard stick into the white powder and with the crowd cheering placed both stick and powder with the nut I’d begun chewing. For a guy who does zero stimulants of any kind, I knew something was up. The fellow then removed the wad he’d been munching from his mouth and excitedly jammed it into my own, this was met by yet another cheer albeit considerably more raucous than the former. I went to stand up but as I did so the whole area began to spin around, I looked at Paul, who had also been plied with the same concoction and stated; “Haven, I don’t think we know what we’ve gotten into!” We were immediately swept up with what must have been the village elders and taken on a tour of each family’s hut as honored guests. We arrived back at our tent in time for a few hours sleep before an early wake up summoned the start of the rally.

Users of betel nut are identifiable by their purple/red teeth, dyed permanently from years of masticating the berries.

Race Day:

Jet helicopters circled overhead as 8-Range Rovers with teams of two co-drivers in each representing Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and the US excitedly waited for the flag to drop. From out of nowhere the villagers whom we’d gotten to know the night before gathered round our vehicle and grabbing its underbelly, literally lifted car and drivers off the ground waist-level while chanting deliriously. No one knew about the international friendship mission conducted the night before, and only later did we overhear a few competitors complaining that one of the American teams had paid for a publicity stunt! Regardless of mixed sentiments at the starting line, we couldn’t have left Mt. Hagan with a better sendoff.

Into the Highlands:

With Mt. Hagan at our backs our third passenger was the sense-of-freedom we’d experienced upon rounding the first bend of our Amazon expedition. Pushing the road conditions, we ascended a gnarly dirt road into a wonderland of plants and species of animals we’d never imagined existed. Some 200-million years ago tectonic plates split the ‘super-continent’ or Gondwanaland. Australia and New Guinea migrated northward, and around 25-million years ago collided with the Eurasian plate causing the two to split. The majority of New Guinea’s plants and animals are endemic, meaning they only exist there.

Due to its isolation, few outside species colonized it, and because of its trajectory, temperatures remained fairly consistent throughout the last Ice Age; this gave wildlife the opportunity to develop into uniquely unchallenged niches. Of the 43-known species of Bird of Paradise, 38 are found in Papua New Guinea.

Collaborating with the unfolding of nature’s wonders, the artistry of indigenous patterns woven into the thatched huts became more ornate the higher we climbed. The mundanity of corrugated tin huts, a telltale sign of modern encroachment at the beginning stages of the rally, gave way to geometric ornateness.

The Take-Home:

As drivers, we were representations of our sponsors, Camel and Range Rover. The prevalent advertising at that time in print and film for Camel was a rough and ready guy dressed in khakis, fording rivers with machete in hand. The Camel Trophy was filmed and chronicled for network and cable television in each of the countries represented, upon returning home we were interviewed on ESPN and a host of other networks from NY to California. On the first day of the rally my thoughts were on anything but iconoclastic add representatives. Looking into the eyes of the indigenous people I saw no facades or pretense, they were completely different from the Western culture I came from. Penetrating deeper into the heart of the forest we came into contact with stone age villages whose people passed right through the 2-foot or so invisible barrier that we maintain with strangers. Akin to an animal sniffing the scent of an unknown entity, they’d come within centimeters of our faces looking deeply while tracing the contours of our eyes, noses and mouths with inquisitive fingertips. I was profoundly moved by their childlike innocence and sincerity. This memory and not the photos of treacherous terrains or artifacts for which we traded our personal knives and flashlights would remain my take home.

Built Tough:

The ingenuity and toughness of the tribesmen were beyond anything we’d ever witnessed. At one point a team using a tire iron was unable to remove the frozen lug nuts from the wheel of their vehicle. Observing the situation and no doubt calculating what should have been ample time to perform the task, a warrior dressed in feathers and facial paint stepped forward and with his bear heel kicked the nuts free. At another point in the rally our cook’s truck missed a turn and rolled down a ravine. A neighboring village gathered and watched with interest as the support crew fastened two fully extended winch cables to the vehicle from their trucks still atop the hillside, but after multiple attempts the foreigners were unsuccessful in winning the tug-of-war with gravity. Sensing the failed rescue the men from the village lined up in single file, each grasping hold of an elongated nylon tow line supplied by the crew, with which the pulled the truck straight up the ravine and back onto the trail from which it had fallen.

A Typical Race Day:

Race days began early. After a quick breakfast the timed departures left camp with no meals consumed en route. Depending on navigation errors, broken parts, winching cars mired in mud up to their axels, blown engines and vehicles rolled over in ditches the size of the machines themselves, the exhausted teams often rolled into the makeshift camps in the dead of night with only a few hours remaining before the next day’s start.

Other challenges required skills in rebuilding broken bridges and passing over them in a 2.6-ton vehicle.

Reoccurring punctured tires with changes rivaling the speed of formula-one pit crews were common. Stopping to help other teams in broken down vehicles at the risk of damaging your own times became a moral question.

Trying to escalate one’s speed when already at full-throttle over rough-cut mountain roads was mandatory, even when sheer drop-offs ensured serious injuries or worse. But we were of an age and mindset of invincibility; not a truism of course but at some stages in life testosterone and being mercifully free from the ravages of intelligence are one’s only protection.

The People We Met Along the Way:

In time nothing surprised us, we grew accustomed to bizarrely beautiful self-expression, decoration and adornment.

The Mud Men:

On one particular afternoon, the course organizers arranged for the teams to arrive in a clearing at the same time. Not sure of the reason for the temporary layover but glad for the respite we climbed out of our Range Rovers. From what seemed to be every angle of the dense jungle perimeter, emerged men with large masks made of clay, pig tusks and dogs’ teeth; their bodies caked in dry mud advanced towards us in an eerie silence. Not wavering in their approach, they continuously struck themselves with the limbs and leaves of some sort of shrubbery. It was apparent that this was an organized display of culture, but with no pre-warning of their existence and the fact that there were more or them than us, it was unsettling. One particular fellow approached a writer for German Penthouse magazine, by the name of Axel Thorer.

Axel’s book on the Camel Trophy, 1000 Miles of Adventure:

Axel was one of my favorite men participating in the Rally, he was large in stature, incredibly friendly and full of life. With his bald head and reddish-blonde elongated mustache, Axel had the quintessential look of a Brewmeister. We watched with anticipation as one of the Mud Men continued his advance towards the much bigger individual in an aggressive manner. But Axel held his ground when the Mud Man grabbed the pen from his chest pocket and jammed it through a piercing in his nostrils. With the ambivalent disdain of a much larger dog eying a significantly smaller canine, Axel deftly extracted the writing instrument in one quick motion and inserted it into the bottom flesh dividing his own two nostrils, parallel and just above the whiskers adorning his upper lip. What none of our team knew about his background, and was certainly not comprehended by the surprised Mud Man, Axel had grown up in Tanga, Tanzania, and had his own nose pierced as a youth! Needless to say, the proverbial ice had been broken and a bond between multiple cultures was forever forged!

The history or legend of the Mud Men passed on verbally from one generation to the next, recounts a battle where their ancestors were defeated by an enemy tribe and forced to flee into the Asaro River. Trying to make their escape after sundown they were spotted by their adversaries, however, because of their mud-caked bodies their foes mistook them for evil spirits and they themselves fled in terror

Boxer Man:

Most of our waking moments were filled with keen focus and adrenaline, but there were times when connections with the locals created special memories. In one crossing of a river not far from a commercial logging camp a small boy, maybe 10 or so, sat on a bridge with a lengthy string tied to his big toe, the other end was fastened to a hook and worm drifting in the fast-moving current. With the camaraderie that one fisherman shares with another, I smiled and looked down from my pilot seat as if to ask how his luck was going, but then spied a previously captured 24-inch rainbow trout lying by his side; the answer was obvious. We’d gained enough time that morning to afford a few minutes from the rally to study his technique. Out of interest we stated the words; President Reagan -- no response, President François Mitterrand – no response, the Pope – again no response, but upon stating Mohamed Ali, the boy’s face lit up and with a huge smile of recognition he excitedly shouted, “BOXER MAN, BOXER MAN!”

You don’t want your man to die:

Whenever we’d come in contact with outlying villages we’d see women from relatively young ages to the very old having faces caked heavily in dried mud. A lighter pasting of the dried clay would cover all other exposed areas. Enquiring as to inclination for the women to be so drably made up and noticeably downcast, we were informed that their husbands had died, and as such they were destined to never marry again and spend the remainder of their lives in mourning.

Last Day:

Up until the last day of the rally we were tied for first, with the final obstacle being a wide river crossing. Calculating the water to be up to our side windows, we hit the river at a high speed to keep the waves of water flowing to the side of the hood. Impossible for us to know at the time, was that our distributor cap was cracked, resulting in the rotors not being able to pass voltage from the ignition coils to the engine's cylinders, which in turn ignited the fuel-air mixture powering our engine. Because of the high-voltage activity the rotor and cap should be replaced relatively frequently, but that was impossible in the nearly impregnable highlands of Papua New Guinea. Progressing at a good clip with the opposite bank in sight our run came to a dead stop, and we had to be winched from the river causing us to drop to an overall third place.

Friendships:

As is the case with any challenging endeavor, meaningful friendships were made with the drivers, mechanics, photographers, route planners, PR representatives, etc. Two of the Italian team were respected Mountain Climbers from the Dolomite range of North Eastern Italy, others were professionals from Milan. A year after the rally I was invited to speak at a gathering of a large Milanese automobile club. The Dutch and Germans were a hearty group for whom we had a great deal of respect. A US photographer by the name of Carroll Seghers II became a life-long friend. We collaborated on several fashion shoots and often discussed how the tie between adventure and fashion could be marketed. Carroll was a leading member of the creative photo revolution in the ‘60’s and ‘70’s, he won several Clio Awards, and his works are included in the Permanent Collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Man as Art:

At the end of the rally and prior to our separate departures, the participants signed each other’s cover page of a book most purchased titled Man as Art, by Malcolm Kirk, published the year prior by Viking Press. My copy remains a special memento with over 30 signatures. Kirk made seven trips to New Guinea between 1967 and 1980 taking hundreds of photos.

Equally impressive as the photographs for me, was the forward of the book written by Dr. Andrew Strathern, an Anthropologist/Andrew Mellon Professor at the University of Pittsburg. As opposed to western culture where our subjective response is stifled by our reliance upon experts and scholars to codify and tell us what constitutes good art, Dr. Strathern explains how the tribespeople are comfortable with their intuitive appraisals. I was so impressed by Dr. Strathern’s commentary that I’ve often quoted him.

Home Again:

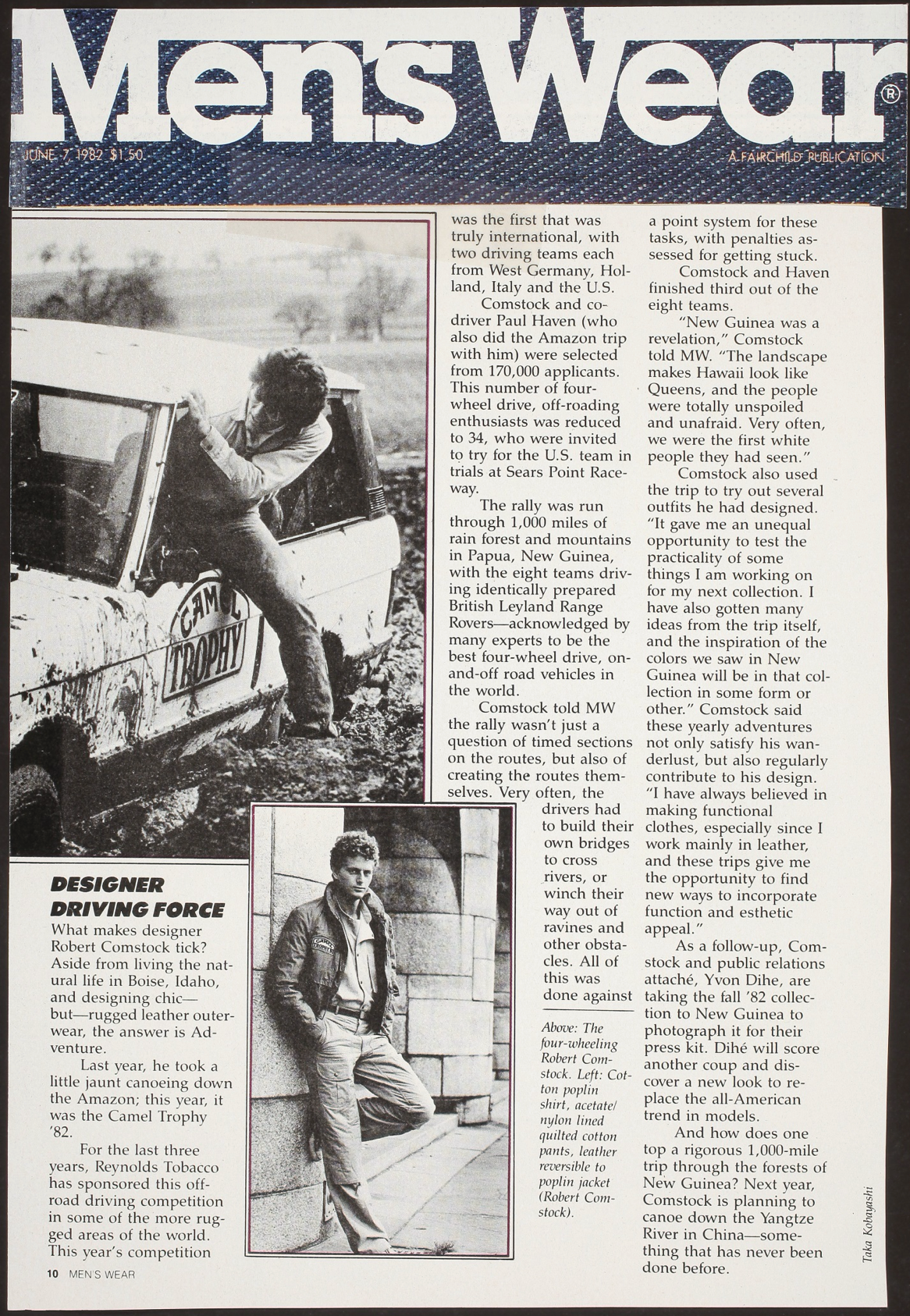

Returning home, my focus returned to my designs and I began to correlate my experiences with the coming year’s collection and the formula that would largely guide my career took shape. A retail group distributing my fashion throughout Japan, closely followed the Camel Trophy and created looks in my shops to mirror the event. The agency overseeing my PR and advertising at the time returned to Papua New Guinea with a photographer, model and stylist. The below image became a billboard in Los Angeles with the following verbiage: "ROBERT COMSTOCK – LIKE EVERY STYLE YOU’VE NEVER SEEN".

Shortly after the Camel Trophy Rally the magazine racks in my local supermarket featured editorials in Car and Driver, Motor Trend, Road & Track, GQ, Playboy and other fashion periodicals; most amusing to me, however, was an article in Popular Mechanics!